RANIKOT

(The largest Fort in The World)

Lieut. Colonel K. A. Rashid

To the North-West corner of Sind in Pakistan, lie the Khirthar range of hills, which stretch between 27'.55° North Latitude, and run South-ward along the Western frontier of the Province to a latitude of 26'.15.° It terminates in the Kohistan Mahal at about 25'.4.3° latitude. The total length of this range is 150 miles, and its general height varies between 4,000 to 5,000 feet above the sea level. The hills consist mainly of lime stone, but sand stone and rubble are also found in plenty. It is calculated that the socks belong to the tertiary system of geological nomenclature.[1] The area is rich in minerals; although not yet fully tapped.

Situated strategically on this range is the largest existing fort in the world called Ranikot. It is known by other names too, such as, Runikot, Ranika-Kot, and Mohun Kot.[2] It lies 18 miles to the South-West of Sann in the district of Dadu. Sann is 56 miles to the north of Hyderabad, in the farmer province of Sind, in Pakistan. Perched high up in the hills, the fort stetches across the hills over a circumference of 18 miles. From a distance, it appears like the Great Wall of China, running sinuously over the hills, valleys and ravines, very tortuous in places, sometimes ascending and sometimes suddenly descending. It is indeed a very skillful work of military engineering.

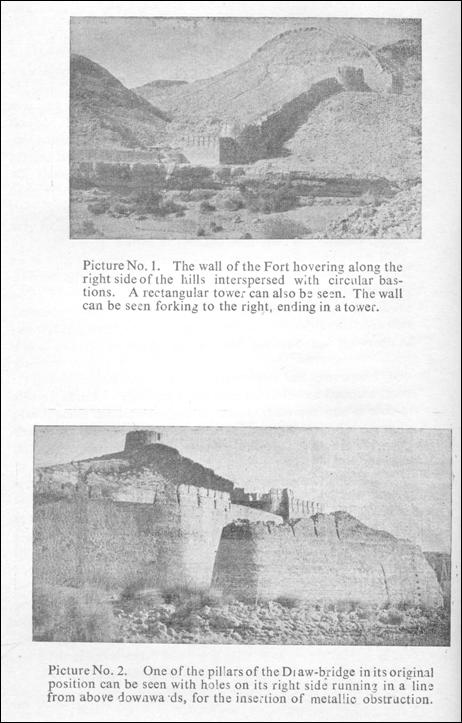

It has a very difficult approach, and the road, which leads to it from Sann, is in a very bad shape. It runs south-west from Sann Railway Station. In fact, there is no roads worth the name, and it takes about an hour and a half to cover this distance of 18 miles on a Jeep. The road, if it may be called so, ends at the fort. As one approaches the fort, one can see the walls of this gigantic structure hovering along the ridges interpersed with circular and rectangular towers to the right and left of a dried stream (Picture No. I).The main gate, if it may be so called, combines in itself the unique characteristics of a gate of entry, a draw bridge, and a dam (non-existent now). After walking through the interior of this fort one can survey its strategic layout which is most amazing. One is forced to come to the conclusion that a long time ago, when this fort was built, this area was a fertile valley through which a stream of fresh water flowed. It was then thickly populated. Sir William Napier in his Administrative Report of Sind says, “Vast tracts of fertile but uninhabited land, and many anciently peopled sites, were also discovered, showing that the riches and mangificence attributed to Scinde in former days were not exagerated, and that the right road was being followed to restore them again. One of those ancient posts was very remarkable. Noted on the maps as Mohun Kote, it is called by Sir Alexander Burnes a fortified hill; but the country people know it by the name of Renne Kote; and it was found to be a Rampart of cut stone and mortar, encircling not one but many hills, being fifteen miles in circumference and having within it a strong perennial streem of purest water gushing from a rock. Greek the site was supposed to be yet no Greek workmanship or ruins were there, and the amears having repaired the walls had the credit of building them.”

Indeed around this stream of clear water had grown up a veritable population. The stream was further reinforced from the Dams placed under the draw-bridges of which there was one at each of the gates called the Sann and the Amri respectively. This served a double purpose; first, it increased the quantity of water in, the valley to form a lake stretching across the entire length of the valley; and secondly, it formed an important part of the defence. Perhaps the fertility of the valley could be revived again by rebuilding the dams at the same places. This fertile flourishing valley must have been a great attraction to the invading armies in days gone by. In order, therefore, to protect it from the intruders the then rulers, whoever they may have been, built themselves a stronghold of such unique dimensions. How long ago this must have been, I am not in a position to assess. But when I come to deal with the date of its construction, I shall put forward my views after taking all aspects into consideration. In the meantime I shall proceed to enumerate my other observations.

THE GATES—The gates are not traditional gates visible from

outside but entrances. This fort has four such entrances or gates; namely : (1) Sann or the Eastern gate; (2) Amri Gate or the North Eastern Gate; (3) Shah Per Darwaza or the Southern Gate; and (4) The Western or the Upper Gate (Mehan Gate).

The Eastern or the Sann gate is known after the name of a small hamlet, which lies to the east of the fort about 18 miles away. The Amri gate is known after the name of Amri, which is archaeologically a very well known and important place. It has been twice excavated by eminent archaeologists and is reputed for its culture. Amri lies 15 miles north of Sann along the Indus river on the main road running to Larkana. This also suggests to us the great antiquity of the fort. This fort perhaps came to be built when Amri was still flourishing and hence the north eastern gate was named after this famous place as was the custom in those days to name gates of towns and forts after the famous places.

The southern gate or the Shah Per Darwaza lies on a lower plane than the Amri gate. The eastern or the Sann gate is the lowest gate ; and finally the western gate is the upper-gate (Mehan gate), which is towards the upper citadel.

There are two more structures situated within the fort wall. They are in the shape of small forts or citadels; one atop the other located at different levels. The lower one is called Miri, and the upper is called the Sher Garh fort. Both these are residential forts and must have been occupied by the head of this dominion, The Miri fort is approximately in the centre of this fortification. It is about three miles from the Sann gate, and beyond this to the western gate is another two miles. The distance has been judged from the travelling time. Thus the diameter of the entire area is five miles. The circumference has been variously calculated as 15 and 18 miles. But it must not be lost sight of that the circumference is not a straight line. It is a tortuous winding wall going up and down the hills. Hughes gives it as 15, whereas Mr. G. M. Syed thinks it is about 18 miles in stretch. From the map reproduced here, the circumference measures 13 miles. This, while going up and down the valley, would come to about 16/17 miles. The two citadels just mentioned are for all practical purposes located almost in the centre of the area, and command a very important strategic position. I shall discuse these two forts later in some detail, when I come to the question of its date of construction The entire valley is visible from these two forts. In time of a military showdown, these two citadels may well have formed the second and the third lines of defence. In addition to these two citadels, there are found two more fortlike structures. One is situated near the western gate, almost adjacent to the wall and the other is near the eastern gate perched high up on the hill. Both the structures are enlarged rectangular towers. The first one is called chan-yari.

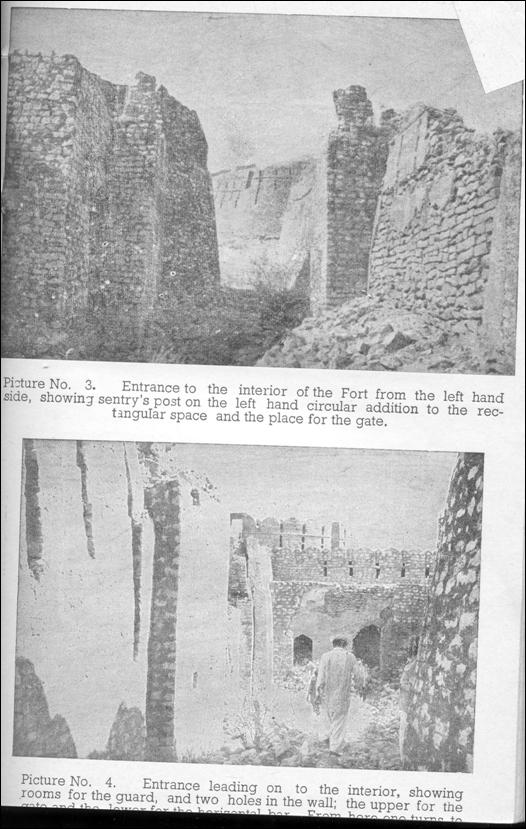

THE MAIN FORT OR THE OUTER FORTIFICATION-The wall is visible from a distance in parts tortuously creeping over the hills and going down into the valley. As one approaches the Sann gate one notices dry stream once full of water, cutting across the middle of it. In places it still has scanty water, which is clear and palatable. On both sides of the stream there are two rounded bastions from which the wall curves upwards and inwards. In the middle of the dry bed of the stream there are two oval pillars, one in its original position, and the other partly broken and shifted away from its exact location (Picture No. 2). These pillars have holes in them on the distal side, which run in a line from above downwards. These holes indicate that metallic bars were inserted between these pillars to which wooden or metallic planks were tied to form a Dam for the obstruction of water, thus forming a lake in the valley. Remnants of this lake are still visible today scattered over in bits in the valley. On top of the pillars wooden planks were placed horizontally to form a Draw-bridge. This enables one to cross from one side of the fort to the other. This bridge was defended by a bridgehead formed by the circular towers on either side of the dry bed of the strea n, which was full, once upon a time. The natural features of the surrounding ground have thus been skillfully utilised. This system of Dan and Draw-bridge is also found at the northeastern or the Amri gate.

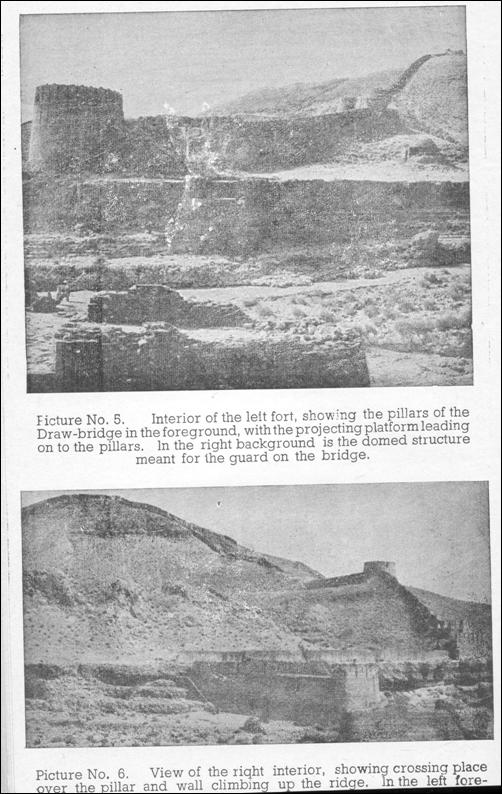

The entrance to the fort from this end is rather a round about one. One has to take a sharp left turn round the left circular bastion to get in. The entrance was thus hidden from sight; and unless one knew about it, it was difficult to locate. There are two circular bastions or towers on either side of the bridge. There are others after them. These have been built by converting the rectangular towers into circular ones. They are a later addition for positioning artillary fire. Originally it appears to me that there were no circular towers at all. This is a very important distinguishing

feature in the assessment of the period of architecture of the fort. It will also be seen that these later additions of rounded bastions are built from sand stone and not the original lime stone of which the entire fort is built. These circular bastions are also not regularly placed along the wall. They are but few and found only in the vicinity of the gates or at the corner of the smaller citadels. Otherwise the original towers were all rectangular regularly placed along the wall. This circular modification has facilitated a double entry gate into the interior of the fort. This double gate system is a Muslim invention which was introduced into Europe by the Crusaders, who had picked it in Syria. The reason for giving a double gate is to create an extra obstacle to the entry. With the rectangular towers there can only be one straight entry.

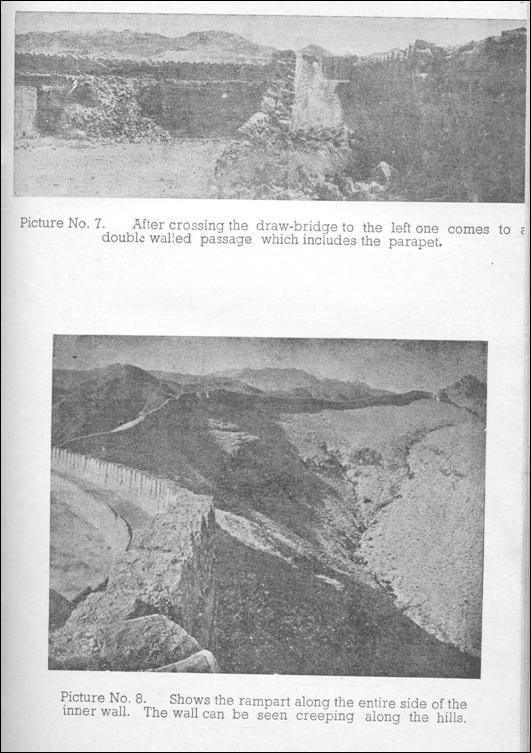

As you enter the fort from the left side (Picture No. 3), you can notice the place of insertion of the two separate gates (Picture No. 4). Along with this and below there is also visible another square hole in the wall for the use of a cross bar to further strengthen the gates. Sometimes a heavy chain was also put across to serve a similar purpose. In this case, I suspect that the chain system was in vogue, because on one side the hole is rather a long one which served for the chain to be pulled in when the gate was desired to be opened. In between the two gates is a rectangular compartment formed by the original rectangle, and a sentry post (Picture No. 3) is noticeable with two guard rooms on the farther side (Picture No. 4). As you cross the second gate you come into an open area, which leads on to the Draw-bridge (Picture No. 5).

To the left of this open area towards the rising hills, one notices a peculiar domed structure of ten square feet area with a door of entry. The dome and the arch of the door are of unusal design. I am inclined to emphasise similarity of this design with the structures found in the Serbian Palaces of the Sassanians. But it also resembles some of the structures of the Tughlaq period. This is only a single room. What could it have been? It is certainly too small for a magazine. But there was no magazine in those days. Can it be the tomb of some one, who was killed heroically and buried here? But there are no sings of a grave either. The room has four niches on each side. I am inclined to think that it was the living quarter for the man who worked on the Draw-bridge. Whatever it may have been, the period of construction of this structure is definitely the same as that of the original fort.

Passing now to the right towards the Draw-bridge on the stream, we come to a platform across which wooden planks were placed to form a bridge over the pillars. One crossed from here to the right side of the fort over the stream. On the opposite side there is also a platform to take similar wooden planks (Picture No. 6). This leads one to a passage on the opposite side which is formed by a double wall, which includes the parapet (Picture No. 7). This double wall is meant to give initial protection to the crossing person.

A rampart exists along the entire length of the inside of the fort wall (Picture No. 8); but the wall is only double for a short distance along the gates. As you cross over to the right side of the fort, and immediately where you alight, there is a flight of steps going down to the stream (Picture No. 6). This was obviously for the purpose of fetching water from the stream, without having to go out of the fort. The wall then proceeds upwards and is seen forking off and ending into a tower (Picture No. 1), the main wall proceeding ahead without any further interruption. There are three circular bastions visible on the right hand side as far as one can see the wall go. and an equal number on the left hand side, terminating in an enlarged rectangular tower at the highest peak of the hill along which the wall creeps. Beyond this the wall disappears into the valley below. These rectangular towers are placed at regular intervals as has been mentioned before. In some places, they are unusually large and in some places they have been converted into circular bastions. It must, however, be kept in mind that the original wall had no circular towers.

The wall is on an average 30 feet high. It is of varying thickness. Near the bastions it is six feet thick. It tapers away from the bastions to a width of five feet. This is exclusive of the thickness of the rampart, which is eight feet wide. This thickness is made up by filling it with rubble. The wall is not upright or straight vertically, but inclines slightly inwards so as to give it more strength. The entire wall is made of lime stone. At the top it has the usual corbel arrangement with the machiolations. Quite a considerable amount of repair is evident. The wall was originally

constructed for the Bow and Arrow warfare; subsequently the machiolations have been enlarged for the lateral play of the crossbow, and perhaps also to accomodate firearms.

This wall, which stretches over an area of 18 miles, is the biggest fortified area in the world, containing two other forts within its perimeter. I say “the biggest,” because this sub-continent has the largest and the maximum number of forts found anywhere in the world; and this fort is the largest of them all. I make this statement after having seen most of them. The Great Wall of China is merely a wall, and does not enclose an area to form a fort; hence it belongs to a different category altogether. A comparison of the architecture of the two will, however, suggest some similarity; and hence I do not hesitate to say that it is just possible the fort of Ranikot may have a direct connection with the builders of the great Wall of China.

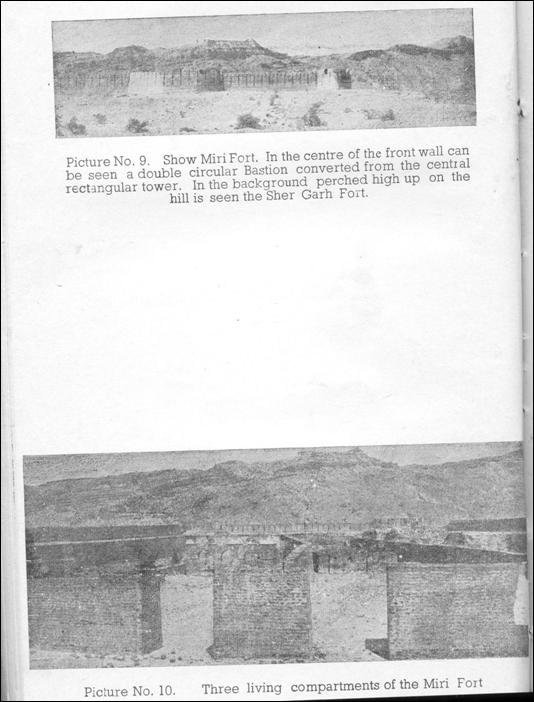

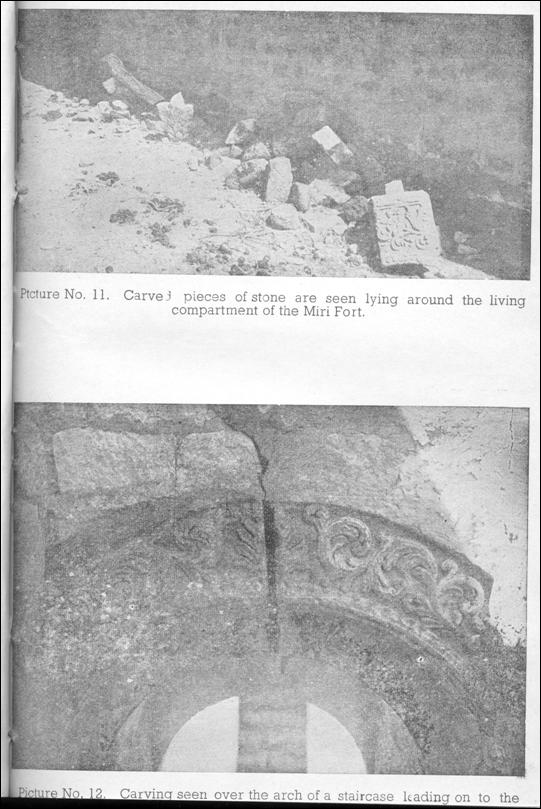

THE CITADELS—Let us now for a while look round the two small citadels situated one atop the other in the centre of this huge enclosure of fortified area. The lower one is called the Miri fort,[3] and the upper one is known as the Sher Garh fort (Picture No. 9). The philology of these two names is not clear to me. The Miri and Lakhshmir-ji-Mari were in fact the palace citadel of the kings, or rather Chiefs of those remote times.[4] Perhaps, they are named after some hero. Sher Garh Fort is the higher and is situated at a height of 1,480 feet above the sea level. The two forts are approximately of the same dimensions, which is to say, about 150 yards on either side. Miri fort is, however, slightly bigger of the two. It is divided into three living areas; each containing living apartments, which are in a bad state of dilapidation (Picture No. 10). These living apartments are certainly of a much later date than that of the actual fort. However, on one side of the left hand apartment, one can see lying several specimens of carved stones with exquisite floral designs (Picture No. 11). These carved pieces are from the original fort, as similar carvings are seen in this fort elsewhere also, strongly fixed in arches and walls (Picture No. 12). The apartments were perhaps built by the Talpurs or the Kalhoras; or may be even by the British during some of their military manoeuvres. I have it on the authority of Mr. G. M. Syed that the British never occupied this fort, and that these quarters were built about thirty years ago. But the carvings from the original buildings denote a Scythio-Sassanian pattern.

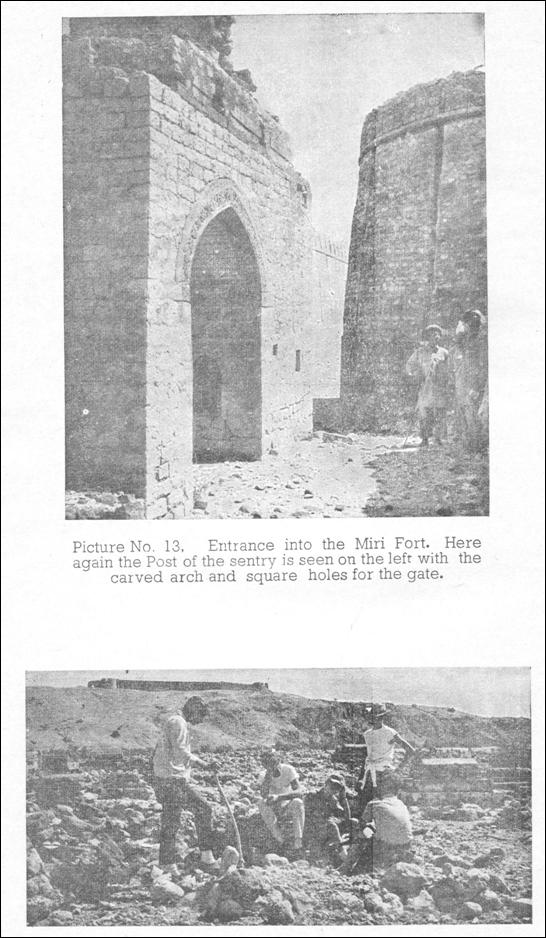

The entrance to these two small forts is very similar to the entrance in the main Sann gate. But the original structure has been altered in the following manner. In the middle of the front wall of the Miri fort there was originally a rectangular tower. This has been extended both towards the right and the left and rounded off so as to form a double circular tower (Picture No. 9). From the outside there are no signs of the rectangle. But as one enters the tower one at once perceives the alteration (Picture No. 13). This procedure has given the entrance a double gate resemblance similar to one I have already described in the Sann gate. This entrance has two arched vaults on either side. The arch is carved beautifully, but the stone on which it is carved is sand stone and not lime stone which is the original material used in the construction of the fort. There are, however, smaller arches present, which are carved on the original stone and are certainly the original pieces of the structure.

The second fort called the Sher Garh fort (the abode of lions) is situated at a much higher level, which is shown on the map as 1,480 feet above sea level. Below this is a graveyard of some significance (Picture No. 14). There are no living quarters inside this fort. This fort is nearer to the western or the upper gate. The famous Sindhi author Mirza Qalich Beg visited this fort as his name is seen inscribed by him on the wall. It is situated on the north-west of the Miri fort. This citadel also has four circular bastions on the four corners. This is a later addition as the original structures were rectangular towers. Towers were made circular at a much later date. Inside these two citadels the wall is double, which is unlike the main wall of the bigger fort, where it has assumed a double shape only near the gates and that too for short distances. This double wall resembles the great wall of China very much in its structure. The machicolations and the palisade are of a variety similar to those of the outer wall.

I have already mentioned about two additional structures in addition to these citadels. One is near the western gate and is about 100 yards by 80 yards, and the second is near the eastern or

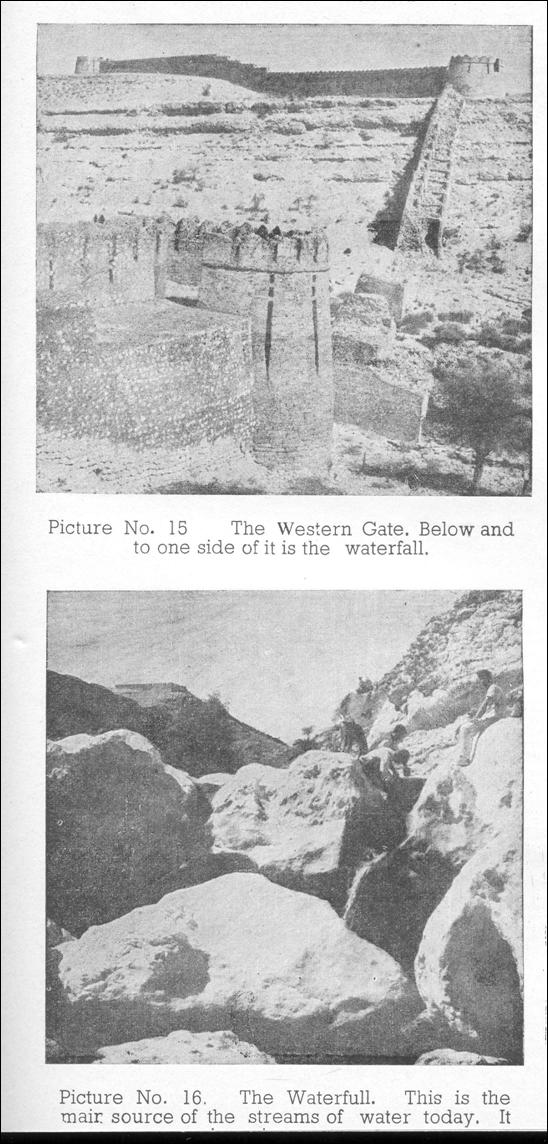

the Sann gate. Both are rectangular. As one approaches the western or the Upper gate (Picture No. 15), one comes to the waterfall from where a small stream of clear water still trickles through, forming into small collections of water inside the valley (Picture No. 16). An area of about 8 acres can also be seen cultivated. At this place the land seems quite fertile (Picture No. 17). This is between the Miri fort and the Western gate. The valley being porous, the water disappears and reappears alternately at several places.

Long before one approaches the Miri fort one can see to the south-west of it a circular bastion projecting over the ridge of a yonder hill. It is a good land-mark for an approach to the citadels. It is a bastion of the southern or the Shah Per gate. Below the Miri fort one can have a good look at the entire valley, which can be seen stretching from east to west. This valley must have looked superb in olden days when the place was inhabited and filled with the choicest aristocracy of trees (Picture No. 18).

PERIOD OF CONSTRUCTION—We now come to the most intricate question about the period of construction of this gigantic monument. Unfortunately the data available to us do not provide any historical evidence of the real architects of this fort. We shall, therefore, have to use our imagination, and concentrate on the architecture itself to determine the period in which it was built. But before we do this, we must keep certain facts in view. Where did the Muslims first learn about the construction of fortification? The earliest Muslim armies passed along a series of Roman frontier forts. They saw them, conquered them and lived in them and modified their designs in later days. Early palaces of Umayyad Caliphs are instances in view. Entrance gates were straight in pre-Muslim days. There are no known instances of a bent entrance during the Roman, the Byzantine or the Persian periods. The history of bent entrances starts with Al-Mansur's city. Tradition attributes the construction of this fort to the TaIpurs. Some have even credited the Kalhoras with its origin. Dr. N. A. Baloch, Dean of the Faculty of Arts, University of Sind, has very kindly sent to me the following note which I reproduce here-unde:

“Regarding the initial planning and the founding of the Runni Kot Fort, no detailed record is available, but the family tradition preserved with the Nawwab family of Talpur (Hyderabad District) gives a fairly clear idea about it as follow: The problem of a stronghold for a final defence against an outside attack had engaged the attention of the Kalhora rulers. Mian Noor Muhammad selected Umarkot for this purpose and rebuilt the fort there and mounted cannons on it. When Nadir Shah attacked Sind, Main Noor Muhammad retreated to Umarkot but Nadir Shah overtook him there. Mian Noor Muhammad could not go any further south because Kuchh, Kathiawar, Jodhpur and Marwar were all Hindu states and there was no hope of any support from them. Main Noor Muhammad had to surrender himself before Nadir Shah.

“The example had proved the futility of having a stronghold in southern Sind, and this was pointed out convincingly by Wali Muhammad Khan Leghari to the Talpur rulers; Mir Karam Ali Khan and Mir Murad Ali Khan, who wanted to build such a stronghold. Wali Muhammad Khan Leghari was a r. an of great talents, an able commander, an engineer, a physician, and a great poet. When the Amirs entrusted him with the task, he selected the present site of Runni Kot. The hill torrent (nainنین)Runni had a perennial spring on this site and the small vale through which it ran was encircled by a fairly high ridge line which had some gaps and holes which could be easily filled up to create a natural fort.

“Wali Muhammad Khan's proposal was approved and the Fort (outer wall as well as the inner fortress of Shergarh and the Miri or the royal residence) was planned and built under his supervision. The only task that remained to be completed was to fit in the gates under the bridge over the Runni. The gates were designed with iron bars but the force of water (in rainy season) simply twisted the bars and the gates did not work. It appears that Wali Muhammad Khan had been appointed as the Nawwab of Larkana and, in his absence, this work was not carried out successfully. In the absence of satisfactory gates, the fort was considered vulnerable and was not occupied finally.

“Mir Hasan All Khan Talpur (d. 1324/1909) in his Fath-Nama (Sindhi Mathnawi) has enumerated the founding of the Runni Kot Fort as one of the outstanding events of Mir Karam Ali Khan's (along Mir Murad All Khan's) rule (1227-1244 A.H.) and described some of its features as follows: Runni Kot is a landmark left by our ancestors. When the plumbers worked at it, they filled in the openings in the encircling hill, from the lowest foundations to the

top, mking it a natural ridge line. Then they made the ridge line even at the top and rised a wall on it—another ridge line on the natural one. It was all stone wall extending in length to Krohs (miles). Flanking on it, hundreds of ramparts (burj) were erected. It was further decorated with thousands of large terraces (Kungra) and innumerable small ones. Another stronghold, called Shergarh, was built inside it. Four ramparts were erected on the Shergarh wall. Still another strong structure, called Miri, was built with four ramparts.

“The nain (hill torrent) flows through the Fort, having water inside the fort area but not a drop outside. This is when there are no rains. Gates on it were necessary for crossing over to the inner fort. They planned two gates, west-eastward, in its bottom. First they raised the stone pillars on the sides and then they fixed the gates. These were iron gates with strong bars. Hundreds of maunds of iron were used, but it did not work. During the rainy season, when the nain Runni flowed for a week continuously, the force of water twisted the bars like ropes. As the gates did not work, the Fort was not occupied. Seventeen lakhs of rupees were spent on the completion of the Fort.”

We will now reproduce below a statement from the Gazetteer of the Province of Sind, compiled by A. W. Huges, in the year 1876. This will throw further light on its history. It runs as follows: “To the South-west of this place (Sann) and on the same torrent, is the vast but ruined fort of Rani-ka-kot, said to have been constructed by two of the Talpur Mirs early in the present century. It was intended as a stronghold to serve not only as a safe place for the deposit of their treasures, but also to afford a refuge for themselves in the event of their country being invaded. This fort is reported to have cost in its erection the large sum of twelve lakhs of rupees, but as the Sann river, which at one time is believed to have flowed near the walls, subsequently changed its course, and caused a scarcity of water in and about the place, it became as a natural consequence uninhabitable, and was, therefore, abandoned. The Sann river, Rani Nai, now runs through the fort and it is stated that no scarcity of water in any way exists.”

Most of this extract is based upon a report made by Captain Delhoste of the Bombay Army, who in 1839 was the Assistant Quartermaster General of that sector. It would perhaps be worthwhile to quote from that report also, before we start to give our own opinion. Here is what the AQMG has said :—

“Rani-ka-kot was built by Mir Karam Ali Talpur and his brother Mir Murad Ali about A.D. 1812, cost 12,00,000 rupees and has never been inhabited in consequence of there being a scarcity of water in and near it—A rapid stream in the rains runs past it and joins the Indus, and by a deviation from its course, parts of the walls of this fort have been destroyed. The object of its construction seems to have been to afford a place of refuge to the Mirs in case of their country being invaded—The river believed to be Sann river, ran formerly round the base of the north face. but about the year 1827 it changed its course, and destroyed part of the north-west wall.” To this Huges adds, “At present the Sann river, or as it is there called the Rani Nai, runs through the fort.” It is possible the fort has been named after this stream Rani Nai as Rani Kot.

Leaving aside the description of the fort, which is mostly correct, I am of the view that the Talpurs could not have been the builders of this fort. They were neither rich nor resourceful to undertake this gigantic construction, They were despots surviving on a Fedual system. Their land was divided into Jagirs under a few chiefs, who in turn supplied them with troops in time of need. They had no standing army. The maximum they could muster was about 50,000 men. In so far as their finances were concerned their revenue was based on a zamindari system, which hardly brought them a share of 35 lakhs of rupees per annum. The total expenditure on construction of this fort as given in the above quotation is 12 lakhs. After seeing the fort, it is impossible to conceive that such a small amount could have sufficed to build this huge structure. I am of the opinion that no less than two crore of rupees were spent on this construction, and it must have taken at least a couple of thousand people employed for a couple of years to complete this job. The finances and the resources of the Talpurs were, therefore, insufficient to meet this expenditure. It is also difficult for me to believe that this fort was built in the year 1812. It was certainly repaired about that time and a few alterations were made. But the fort is certainly a much earlier construction. My reasons for saying so are as follows:—

(1) The Corbles and the machiolations are of pre-gun-powder period and meant for bow and arrow warfare.

(2) The serpentine outer wall is interspersed with rectangular towers, which were in vogue before the 10th century of the Christian era.

(3) The naming of the eastern gate as the Amri gate shows that Amri was still flourishing when the fort was built and not buried under the ground as in the last century.

(4) The carvings in the Miri fort are of Scythian artisticpatterns.

(5) The dome-shaped structure in the interior of the entrance at Sann gate belongs to Scythio-Sassanian period.

(6) There is a very great resemblance between the Great Wall of China and Ranikot, thus indicating an older period of construction.

The Talpurs and the Mirs have also used this fort for their residential perposes, and perhaps for refuge too in tmie of need. Another important fact which should not be lost sight of, is this: the Talpurs and the Kalhoras built forts which are to be found on the eastern side of the river Indus, and not on the western side. The repairs and alterations which they carried out in this fort were during their differences with the Kalat state. But the actual construction of the fort must have taken place a long time before that. I shall presently attempt to place its date of construction in an appropriate period by further arguments.

This construction in my opinion was necessitated by the population that lived around the fertile valley inside the existing fort. Actually there had existed habitation in the valley from time immemorial; and as the valley was very fertile it was very attractive too. Therefore, at some time in history, the rulers who were permanently settled here, in order to safeguard this place, built themselves a fortification with citadels located in the middle of the valley positioning them very strategically. These small forts or citadels must have also served as the second and third line of defence in time of an invasion as I have already pointed out. To have brought people from outside to build this fort would have entailed a great deal of hardship in the way of their sustenance. Of course there must have been some prisoners also to assist them, and some skilled artisans.

There are indications of habitation below the upper citadel Sher Garh. This is in the form of a huge graveyard. There are some graves with tomb stones and sarcophagus and some ordinary ones (Picture No. 14). There is no doubt that people did live in this valley. Although signs of habitation are not traceable today, it is probable their houses have been washed away by heavy rains. Perhaps some further excavations may reveal the site of earlier habitation. To me it appears that this valley had been rendered desolate much before the time of Huges and Captain Delhoste. It may even have happened earlier than the time of the Talpurs and the Kalhoras. As 1 visualise the whole episode, it appears to me that a very long time ago in history, the draw-bridges at the Sann and the Amri gates were demolished by floods caused by heavy rains or by an attacking army, thus letting the water out and drying the area. The population was hence forced to abandon the place. The stream of water which exists to this day in places shows that it is a clear stream of pure water originating at the small water-fall near the western gate. In olden times this stream was large and the water gushed through it to collect in the lake in large amount due to the Dam under the draw-bridges. As this water from the lake rushed past, the alluvial soil must have been taken away with it and so also the subsequent rains must have taken away some, thus rendering the entire valley barren leaving a loose soil full of bolsters underneath, upon which nothing could grow except the desert vegetation.

Now let us come to the real question. Who built tie fort ? I must admit that I have been unable to arrive at a definite conclusion. But there are various possibilities, which come to my mind. As to the fort's antiquity, I have enumerated several arguments above. In order now to pin-pont the period of its construction, we shall have to deal one by one with the different periods in history. Let us take them together in order of priority, and discuss the the feasibility of each one of them. They are as follows :‑

|

The British |

1857-1947 |

AC |

|

The Talpurs |

1783-1857 |

“ |

|

The Kalhoras |

1700-1783 |

“ |

|

The Moghuls |

1500-1700 |

“ |

|

The Tarkhans |

1450-1550 |

“ |

|

The Arghuns |

1350-1450 |

“ |

|

The Sumas |

1325-1350 |

“ |

|

The Tughlaqs |

1310-1325 |

“ |

|

The Sumras |

1225-1310 |

“ |

|

The Tartars |

1000-1225 |

AC |

|

The Scythians |

200-100 |

BC |

|

The Parthians |

100-50 |

“ |

|

The Sassanians |

325-50 |

“ |

|

The Greeks |

325 |

“ |

Out of this list I have already ruled out the first two. The British were not mentioned, but they can also be brushed aside; for they built no forts in this subcontinent. The Moghuls can be set aside as it is not a Moghul architecture at all. It has none of their pecularities. The Tarkhans, the Arghuns, and the Sumas were in the Delta of Sind as small feudal lords, and only built round Thatta; in fact right upto the Tartars they were all here for a short period, and in transit. Feroze Shah Tughlaq appears to have come this way a number of times and even built a lake Sangar. He paid a courtesy call on the famous saint of his time known as Pir Lal Shah Baz. It appears to me that the architecture of Ranikot fort may have some resemblance to the architecture of the Tughlaq period and with the older forts he built in India. The Hindus can also be ruled out, as fort building was not known to them in the pre-Muslim days.

Passing down to the Scythians, we find that they were no invaders. They had come to settle down. A branch of theirs came direct to the south from the north along the river Indus and settled down in Sind. They are known in history as Indo-Scythians. The Scythians come from Central Asia, and were a branch of the Aryans. It is possible they may have brought with them the knowledge of the Great Wall of China; this great fort of Ranikot does resemble it in many ways. It will be interesting to note that Scythio-Parthian remains have been discovered in Bhambhor. The outer fortification has been cleared in three tiers, one atop the other. The walls are interspersed with circular towers alternating with rectangular towers. This is, identical with the architecture of Ranikot. I presume, this is a pre-Muslim structure; for the Muslims at the time of the invasion of Muhammad bin Qasim were unaware of any defensive architecture. They came across this during Crusades while in contact with the enemy along the frontiers of Iraq and Syria, where Roman fortifications were found. I am inclined to believe that Bhambhor fortification is a Scythian structure just like the fort of Ranikot. Even today in Sind a large proportion of the population is Scythian. The rest of them are Semetic.

The Greeks can be ruled out due to their very short stay. Alexander himself did not spend more than four years in the subcontinent. He had no time for constructive work. He was an invader, who hurriedly went back with his conquering army, which had become homesick.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS–I

am grateful to the undermentioned persons for assisting me in my journey to

Ranikot or helping me to acquire material to write this dissertation. First of

all my thanks are due to Mr. William Abbe of the Usaid (CENTO Gp.), who inspired

me to undertake the journey and later by very kindly lending me a few

photographs, some of which are reproduced here. Secondly, my thanks are due to

my learned friend Pir Hassam-uddin Rashdi, who not only accompanied me

throughout the journey, but also arranged for tranport to take us to our

destination, and later by lending me books from his library. It was through him

that I was introduced to Mr. G.M. Syed, whose hospitality we enjoyed for a

couple of days in Sann. For the use of books I am also thankful to Dr. F. A.

Khan, Director of Archaeology, for allowing me the use of his Directorate's

library. I am also thankful to Dr. N. A. Baloch, Dean of the Faculty of Arts,

Sind University, for supplying ire information reproduced here. I am also

thankful to Mr. G. Ahmad Mufti for typing out the Manuscript.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1) Gazetteer of the Province of Sind. E. H. Aitken, Mercantile Steam Press, Karachi, 1907.

2) Gazetteer of the Province of Sind, A. W. Huges, George Bell & Sons, London, 1876.

3) History of General Sir Charles Napiear's Administration of Scinde & Campaign in the Cutchee Hills, Lieut. General Sir William Napier, Chapman & Hall, London, 1851.

4) The Strongholds of India, Sidney Toy, William Heinemann Limited, London 1955.

5) A History of Fortification, Sidney Toy, William Heinemann Limited, London 1955.

6) Historical Dissertations, Lieut. Colonel K.A. Rashid, Pakistan Historical Society, Karachi, 1962. Chapter, “Military Architecture in Pakistan.”

7. Sind, General Introduction, H. T. Lambrick, Sindhi Abadi Board, Hyderabad, Pakistan, 1964.

8. The Seventh Great Oriental Monarchy, George Rawlinson, Dodd Mead & Company, New York, 1875.

9. Encyclopedea Britannica, University of Chicago, 1949 Vol. 9.

10. Indian Architecture (Islamic Period), Percy Brown, Taraporewala, Bombay, 1942.

11. “Fortification in Islam before A. D. 1250”, K.A.C. Creswell, Paper published in the Proceedings of the British Academy, 1952.

NOTES

[1]

E. H. Atken, Gazetteer of the Province of Sind, Karachi, 1907. I

have my doubt

about the height. The survey of Parkistan Map No. 35

![]() gives the contours

between 500-2,000 feet.

gives the contours

between 500-2,000 feet.

[2] A. W. Haighes. Gazetteer of the Province of Sind, London, 1876.

[3]

In the Survey of Pakistan Map No. 35

![]() it is named as

Ameri Kot, height 837 feet above sea level.

it is named as

Ameri Kot, height 837 feet above sea level.

[4] H. T. Lambrick, Sind General Introduction, Hyderabad, 1964.

![]()