An Introduction Of The Ms Available At

The Mevlana Museum, Konya, Turkey.

Prof. Dr. Erkan Turkmen

In my previous article (Maulana Ahmad Husain Kanpuri and Indian Commentries on Rumi’s Masnevi) published in the Islam and Modern Age,

Journal No. XXXV, February 2005, I had drawn attention of scholars to Masnevi’s most authentic MS available at the Mevlana Museum Konya, Turkey (reg. No.50). A facsimile of the same has been made available in three different sizes by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Turkey, 1993 (ISBN No. 975171452-4). This time, I shall like to throw more light upon the MS as it can be essential source for the scholars:

When Masnevi traveled from Konya (Central Anatolia) to Iran, Afghanistan and India, many changes were made in the verses of the work by scholars and scribers, which have to be taken into consideration before any further research is planned. These changes can be divided into three groups: 1- Usage of defective MSS 2- Failure to comprehend the mystic meanings of the terminology 3- Changes introduced under the impact of the local traditions and beliefs.

1- Usage of defective MSS:

The earliest scholars who began to search for an accurate MS were Abdulbaki Gölpınarlı from Turkey (1), Nicholson from England (2) and Feruzanfer (3) from Iran. Nicholson, most probably due to the Second World War, could not visit Turkey to see any MS personally. Luckily, the MSS he received by post were not very different from the MS of the Masnevi of Museum, yet not perfect. Abdulbaki studied it, but made no critical edition or clarified the variants in details, although he made full use of the MS while rendering his translation into Turkish.

Nicholson did not go into essential references of the Koranic verses and relative Hadis relating to the Islamic Sufism (Tasawwuf) that form the fundamental frame of Rumi’s Masnevi.

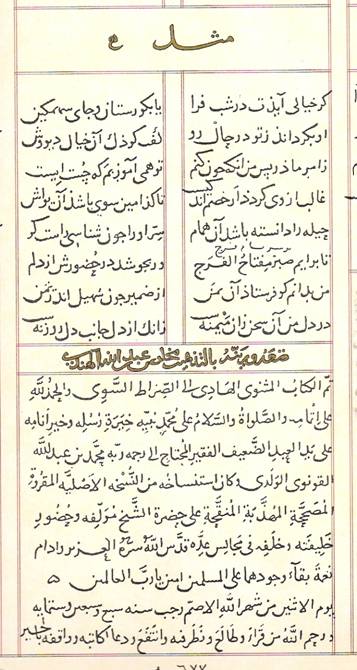

MS of Mevlana Museum has 325 folios, each 49 x 32 cm. Rough English of the colophon is:

“The illumination of it (the MS) has been made by humble Abdullah al-Hindi”

(The above lines are in the rubric)

“This book of Masnevi, which is a guidance to the path; thanks to God and peace be upon Prophet Muhammad, has been completed by the hands of humble slave (of God) and who needs His mercy Muhammad bin Abdullah al- Konavi and disciple of (Sultan) Weled(Rumi’s son). This manuscript has been copied from the original MS that had been corrected by the sheikh and the author (Mevlana Jelal al-Din Rumi) and his khalife (Husam al- Din Chelebi) during some meetings. May God disclose his (Rumi’s) secrets on Muslims continuously.

Completed in the sacred month of Rajab 670 (October 1278) when God has more mercy on the readers who look at it (the MS) and they may pray for the scriber”.

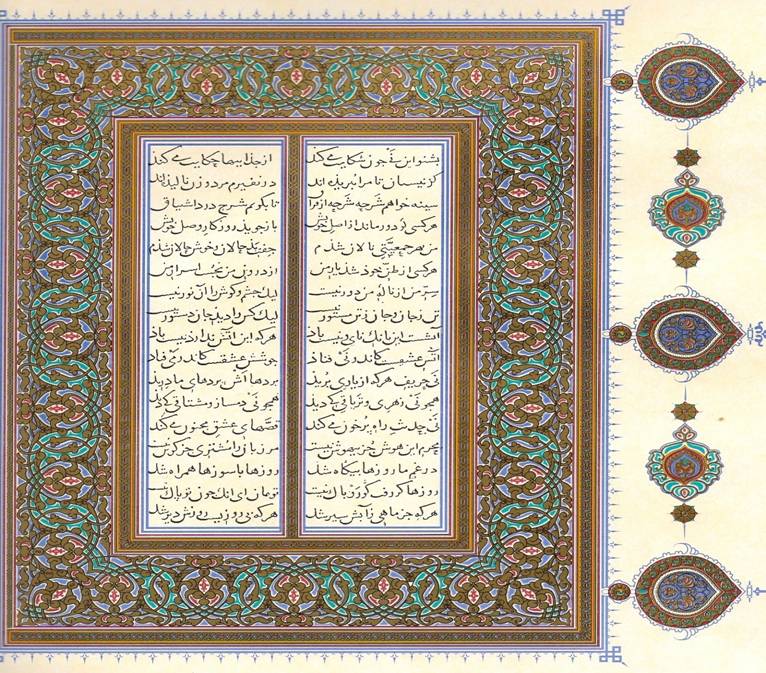

The very first verse of the MS is:

بشنو اين نى ﭼو ن شكا يت مى كند از جد ا ئها حكايت مى كند

And it is quoted by Eflaki Dede (author of the Manaqib al Arafin)(4)a decade after the death of Rumi exactly the same way. It was changed later as:

بشنو از نى ﭼو ن حكا يت مى كند از جدائها شكايت مى كند

Accurate translation will be “Listen to this Nay (Rumi himself) while it is complaining and telling the story of separation (from its Origin = God). Here “The story of separation” is better than just “complaining”. In the second line we see “der nefirem” and not, “az nefirem”. Here again “der nefirim” suits the first line “een nay”, and is more emphatic as it means “in the presence of the nay (Rumi himself)”. As a mater of fact, the Nay of the eighteen verses is Rumi’s own spiritual state, misunderstood by the fanatic groups in Konya. His Masnevi being non dimensional interpretation of the Koran was not understood by the common people (awam). This is why they tried to kill his spiritual master Shams, whose teachings and interpretation of the Koran were alien to them. Sufi’s Sema (transcendental dance) accompanied with music was shamanistic performance, and for them it did not seem to fit the Islamic way of life. Many fanatic Muslim scholars tried to hide such mystic elements by changing the meaning of the Masnevi. They also do the similar thing with the interpretation of the Koran.

There is another old manuscript available at the Yusuf Agha Library, Konya (Reg.No.5547). This MS was previously dedicated to the Shrine of Rumi’s mother (Madder-i Mevlana Musuem) at Karaman. It has variants in the margin that belong to Husameddin Chelebi (shortened as ‘Husam’) and to Sultan Weled (shortened as ‘Weled’). This makes the MS first critical edition of the Masnevi. It also throws light on the Sufi terms used in the work with the meanings as understood those days. For example the fourth line is:

هر كسى كو دور ما ند از اصل خويش باز جويد روزﮔار وصل خو يش

(He who falls away from his origin, seeks for an opportunity to join it again)

To explain the right meaning of the word “Origin”, “Hubul al watan min al iman = Love of country is a part of belief (Words of Prophet Muhammed)” has been given in the margin, which refers to the original land (vicinity) of God (i.e. the reed land) where man was once fresh and ever green like the reed of the flute by being watered with divine love and light. Now, separation from that land has made man (the flute) lonely and deserted. The spirit (breath of God) yearns for the Blower as the Koran says, “…I breathed into man my breath” (the Koran XV/28, 29). This breath (trust) man carries within him (Koran 33/ 72); and when he discovers the breath (trust of God) in him, he begins to look for God and feels like fish out of water. But he whose holes are blocked, like the imperforated reed of the Nay with worldly desires and strong ego, does not feel breath of God in him; and thus has no feelings of separation.

The Yusuf Agha MS supports the above explanation by giving meanings of the terms Mahi (fish) and Nistan (the reed land) in the margin as: “juz mahi = ashiq nist” (not in love) and “hubul watan=love of country”.

Again, we learn through the Yusuf Agha MS that the Hadis of Muhammad, “Believers (Muslims) are each other’s mirrors” has been referred to by Husam as:

پيش ﭼشمت د اشتى شيشه كبود ز آ ن سبب عالم كبو د ت مى نمود

(You have placed blue piece of glass in front of your eyes, and because of that you see the world blue).

But Weled gives the verse as:

جام روزن سا ختى شيشه كبود نور خور شيد كبو دت مى نمود

(You have placed blue glass on your window; therefore, the light of the sun looks blue to you).

Both sound alright but Husam’s suggestion seems to be more logical.

Here is another example: The verse found in the story of ‘A Parrot and the Grocer’ is as follows:

مى نمود آن مرغ را هر ﮔون شكفت تا كه باشد كاندر آيد او بکفت

(He showed all sorts of strange objects to the bird, so that he may begin to speak). (Nicholson Edition).

While the MM gives “Her gun shegoft”(all sorts of strange objects) and in the margin “Sad gun nehoft(hundreds of hidden objects) but Y.A. has only “Sad gun shegoft= hundreds of strange objects …” which sounds more suitable.

In some cases, Nicholson Edition (MI/1247) differs a lot:

ﭼو ن ملك انوار حق در وى بيافت در سجود و در خدمت شتا فت

When the angel found God’s light in him (Adam), he prostrated himself before him and hurried to be in his service.

The Yusuf Agha has:

ﭼون ملائك نور حق ديدند ز او جمله افتا دند و در سجده برو

When the angels found God’s light in him, they all fell down and prostrated themselves before him, face down.

I think the second form sounds better, because it suits the statement of the Koran.

Sometime we come across verses missing in Nicholson’s edition. For instance, there are four verses missing after the verse No. II / 3325 and one of them, being interesting, has been given below:

حوض با دريا ا ﮔرپهلو زند خو يش را از بيخ هستى بر كند

If a water pool begins to struggle with a sea, it uproots its own being.

In the above line by the sea God’s lover (Awliya = a saint) or God Himself is meant.

2- Commentaries that fail to grasp the mystic depth of the terminology of the Masnevi:

Examples above show that Masnevi cannot be understood without grasping the mystic terminology of the Koran. At first glance, many terms used by Rumi may seem to suit Hinduism, Buddhism, Greek Philosophy and others but they all agree with the mystic dimension of the Koran and tasawwuf (Islamic mysticism) ‘Nay’ or Bansari may remind us of Lord Krishna’s magical charm, but according to Rumi it is human body with breath of God in it.

Masnevi is truly an indirect interpretation of the Koran as said by Molla Abdurraham Jami, although Mr.Nicholson does not seem to agree with him.

To grasp the real meaning of the Koran or Masnevi we have to pass from the akl-i juz (individual wisdom) to the akl-i kul (universal wisdom) and thence to the divine wisdom (‘the ocean of divine wisdom’ as named by Rumi). When we reach the divine wisdom, which is pure and above all negative feelings, we begin to love every creature, and religions fall behind as Rumi says:

ملت عشق از همه ملت جدا ست عاشقانرا ملت و مذ هب خدا ست

Nation of love is different from all other nations; their religion and belief is only God.

Some Indian commentaries try to show Rumi as fatalist (5). This is against the teachings of the Koran and the teachings of Rumi, who was against the Jaberiya (the fatalist). Rumi suggests action and vitality as it is said in the Koran, ‘Wa ina leysalil insana illa mas’a= Man is man to the extent he struggles and labours’ which is certainly better than: ‘Cogito ergo sum= I am thinking, so I am’. So, the addition of the verse in the Indian MS as ‘Fikre ma der kar-e ma azare mast= Pondering over our deeds is only a self torture’ is against the Koranic teaching and, therefore, against Rumi’s philosophy. Rumi in contradiction to the above verse says this:

ﮔر توكل مى كنى در كار

كن

كسب كن پس تكيه بر جبار كن

خواجه ﭼون بيلى بدست

بنده داد

بى زبان معلوم شد او را مراد

(M I / 947-948)

f you trust in God, then work hard; keep on working and put your faith in Jabbar(the over powering Lord); if a master puts a spade in your hands, without any words his purpose is clear (here spade means two hands given by God).

More additions in Masnevi began to appear after Ibrahim Gulshani (16th century scholar) in the Iranian and Indian MSS. Some scholars raised the number of the first eighteen verses to 22. Others transferred some verses from the sixth volume, and some invented them. For example:

آنﭼه مى ﮔويد اندر اين دو باب ﮔر بﮔويم من جهان ﮔردد خراب

If I say what this (the flute) is saying about the two worlds; this world will be devastated.

سر نهانست اندر زير و بم فاش ﮔر ﮔو يم جهان بر هم ز نم

Secret is hidden in the highness and lowness of the sound; if I disclose it, I may devastate the world (6). Naturally, if new words and verses are added to the Masnevi, the commentaries will also be misleading.

3- Some commentaries indulge into superfluous details that make them insipid and boring. As shown above, they also depart from the Koran and Hadis that are the main source of the Masnevi and plunge into Greek and Hindu philosophies. Such commentators could look up at the Koran first and then bring in examples from other religious books or philosophies.

In India, Masnevi never lost its impact on the Indian mystic poets even until Muhammed Iqbal; and the commentaries provided source of unlimited love of God that carried them beyond the boundaries of physical barriers to eternal knowledge of God (Ilm-i ledun). Even Asadullah Khan Ghalib, who is supposed to be as secular as Shakespeare, wrote replica to Rumi’s First Eighteen Verses under the title “Surme-yi Binish = The Eyeliner of Vision” in which he tries to give the main idea of the Masnevi.

The Indian commentaries had three major purposes. Some tried to solve subtle mystic terminology for the students of Persian language in India because after the Turkish rulers such as Karakhanids, Seljuks, Ghaznevids, Khuwarezmis, Shemsies and Baburies used Persian as their official language. It was not possible to obtain any degree in India without learning Persian like Latin in Europe. To this end, many commentaries aimed at teaching Persian, and what could be better than to teach Masnevi that gave a universal message to all the religions available in India. However, some commentaries had higher aim of teaching Tassawuf (Islamic Myticism) by means of Rumi’s ideas and stories much familiar to an Indian mysticism. Other commentaries were written to teach Koranic verses and the Hadis (Sayings of Prophet Muhammad). According to the belief of the commentator the explanation would lead to Hama Ust= everything or being is God or Hama az Ust = everything is from God. Rumi did not believe in Hama Ust because this universe and creation is only a small part of the Whole as he explains in the story of the elephant in the darkness.

As a result, it will be safer to use the facsimile of Mevlana Museum MS, and for mystic terms and the explanations of Yusuf Agha MS.

Note: Another remarkable point about the Mevlana Museum MS is that it had been illuminated by an Indian artist Abdullah al-Hindi. We do not know any thing about the gentlemen’s life. However, it can be guessed that there some Indian scholars and disciples of Rumi in Konya, who might had come from Afghanistan with Rumi’s father. There are stories about elephants, tigers, parrots and other Indian elements in Rumi’s Masnevi.

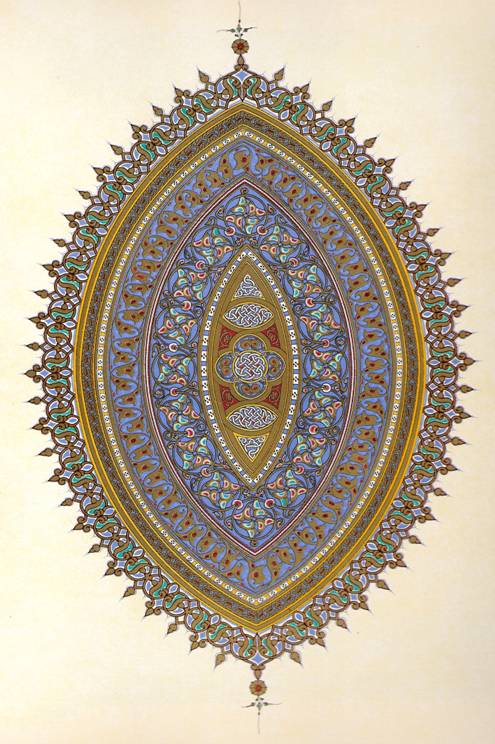

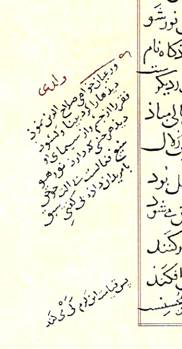

The drawings and illuminations have purely Indian taste. There is a Jin Jan motif drawn in the centre of the flower.

Notes and References

1- Abdēlbaki Gölpınarlı, Mesnevi Tercēmesi ve Şerhi, İnkilap Aka Kitabevi

İstanbul, 1981.

2- R.A. Nicholson, The Mathnevi of Jellalu’ddin Rumi, Luzac and Co., London.

3- Bedi’uzaman Feruzanfer, Sherh-i Masnevi-yi Sherif, Tehran 1373 and Kerim Zamani, Sherh-i Jami Mesneviyi Manavi, Istisharat-i Itla’at, Tehran 1374.

4- Ahmet Eflaki, Tahsin Yazıcı, Manak al-Arifin, Tērk Tarih Kurumu,

Ankara, 1959.

5- For details see Erkan Tērkmen, Maulana Ahmad Huseain Kanpuri and

Indian Commentaries on Rumi’s Masnevi, Islam and Modern Age, Vol. XXXV February 2005 and The Essence of Rumi’s Masnevi, Ministry

of Culture, Ankara Turkey.

6- Movlana Nazir Sahib, Muftah al- Ulum,Sheykh Ghulam Ali and Sons,

Lahore.

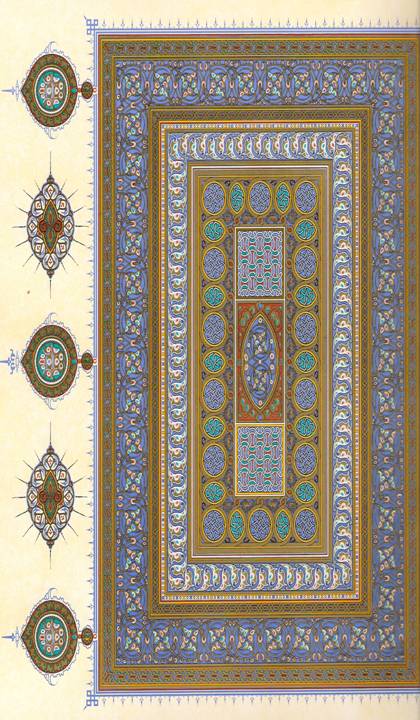

The carpet design with meaningful figures.

Attached side flowers with Jin Jan in their centres. Representing the idea that everything is known by its opposite.

The divine eye with eyelashes.

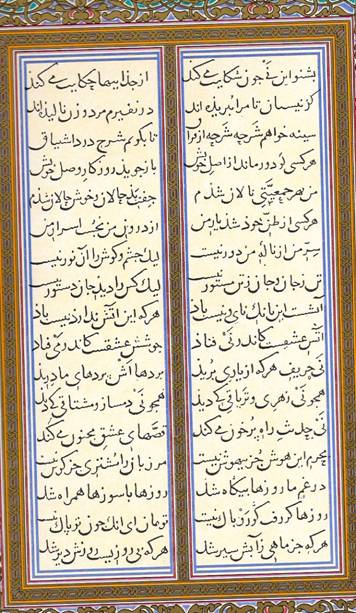

First page of the MS.

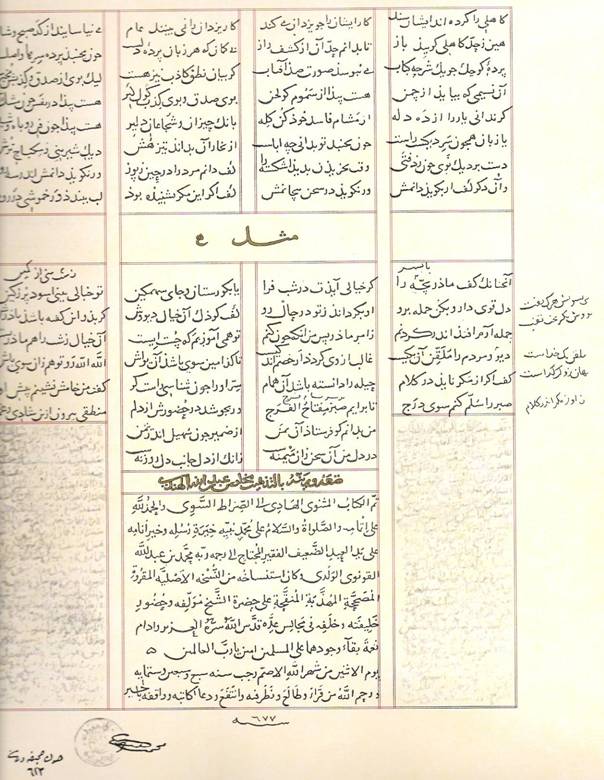

Another view of the first page of the MS

The colophone

Another view of the last page.

The verses added by Sultan Weled in the margin and signed as “Weledi’.